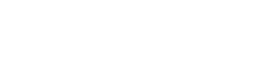

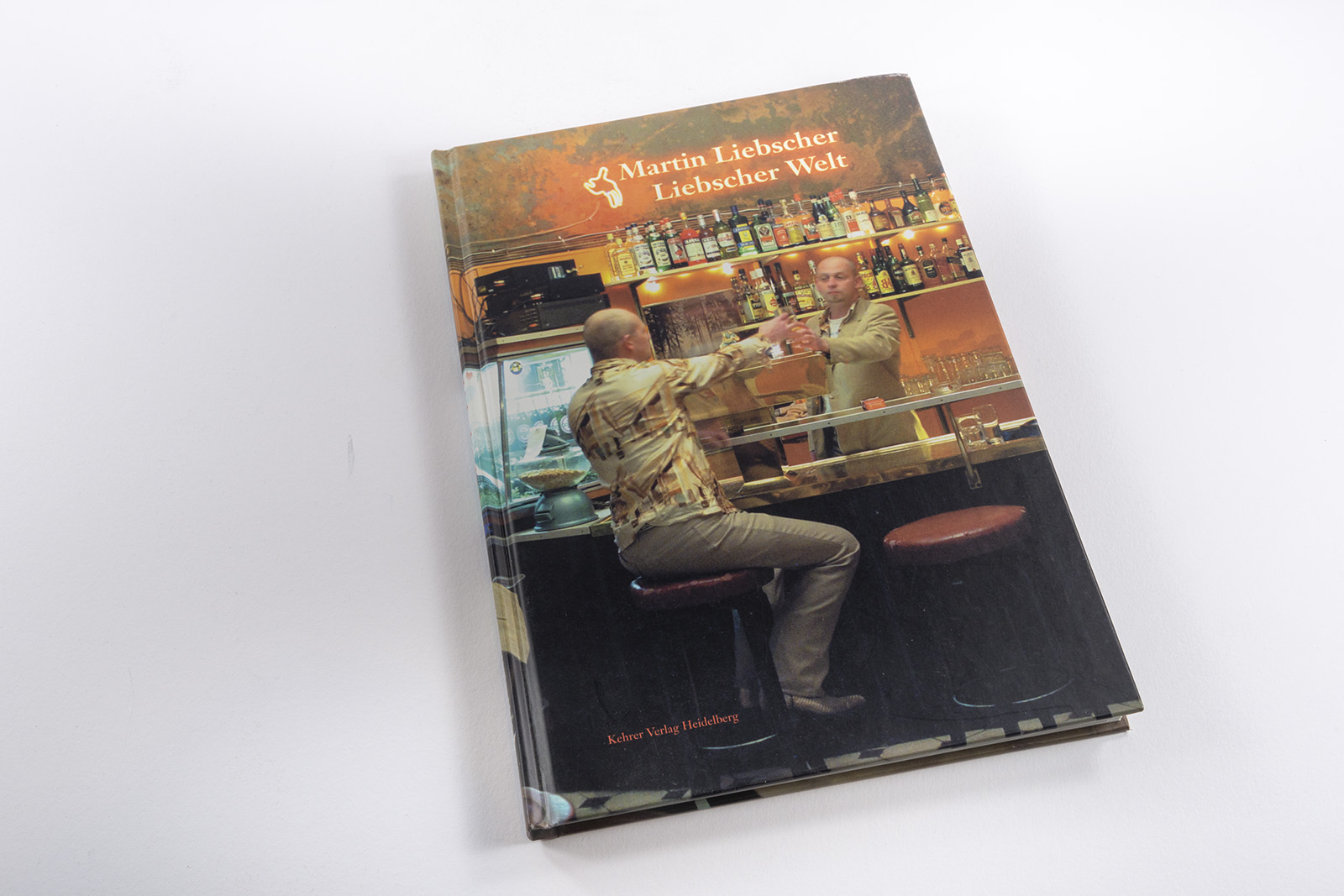

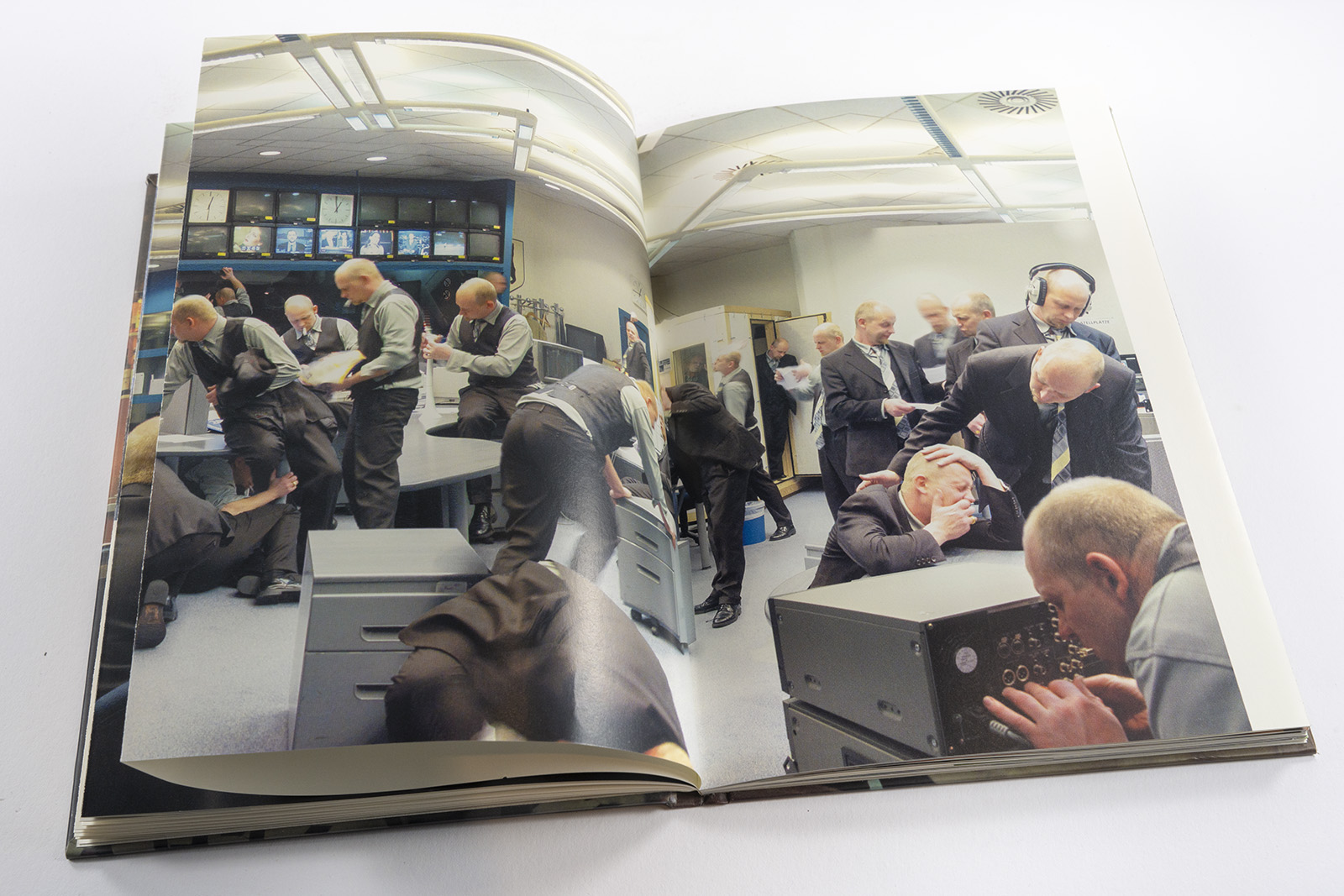

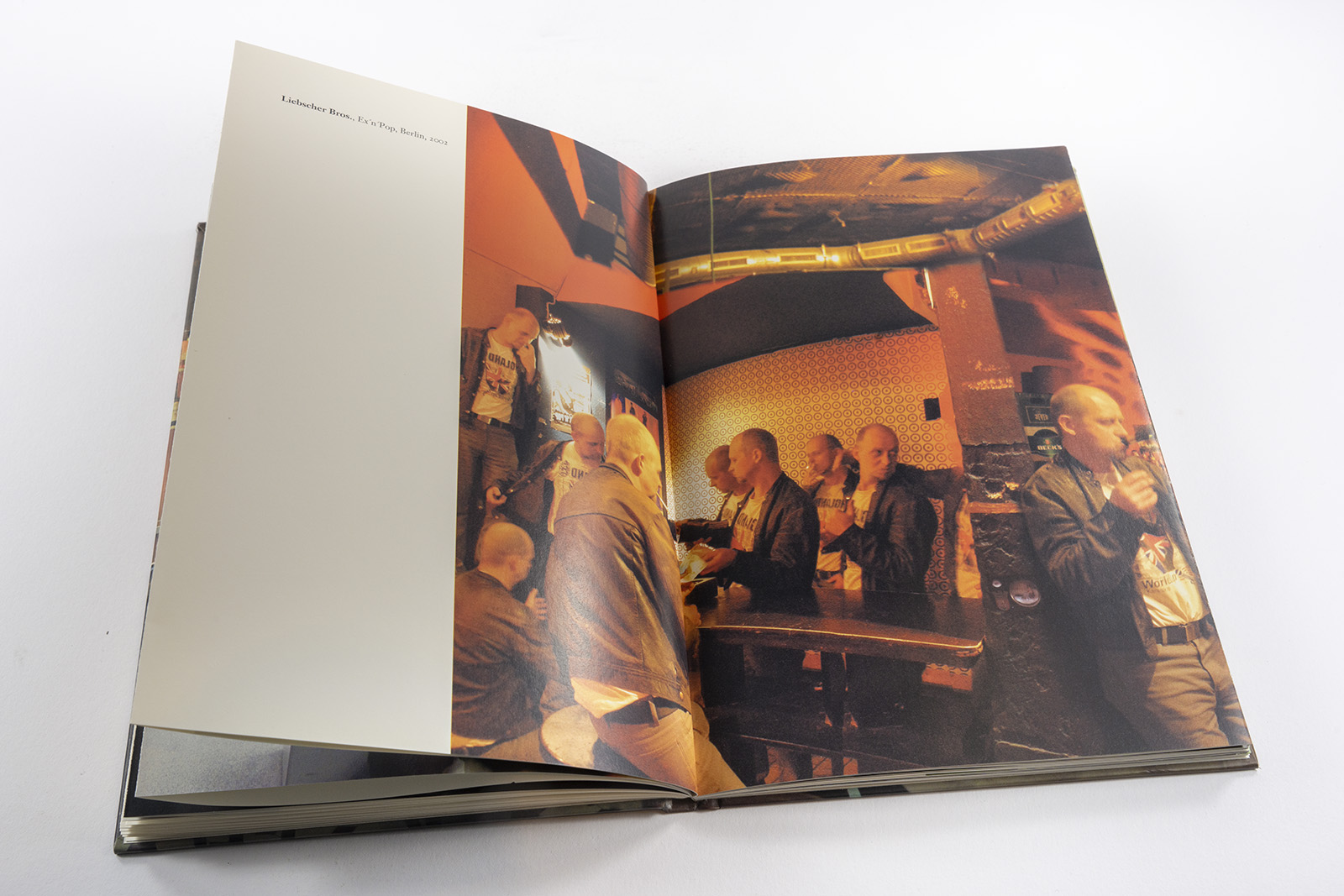

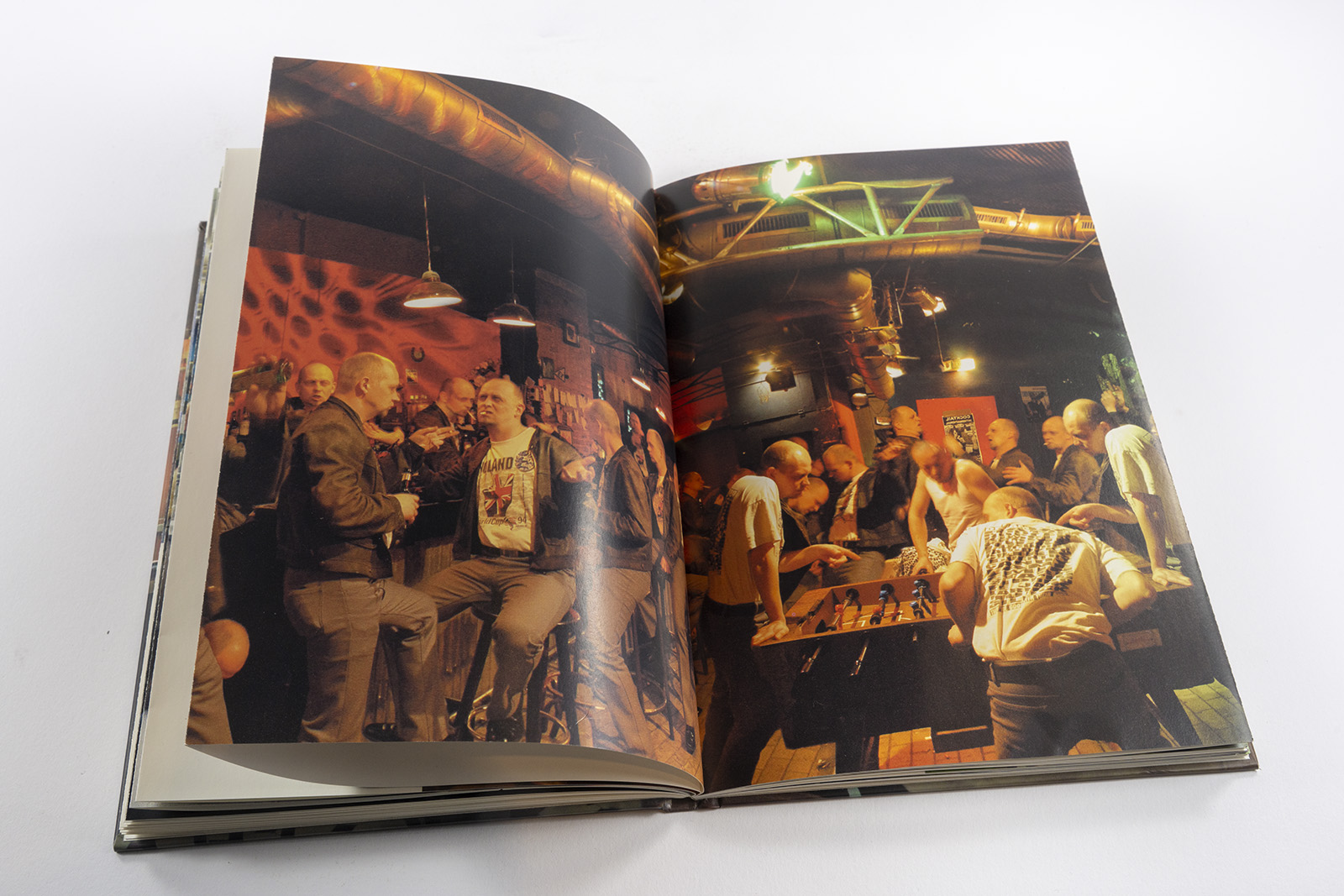

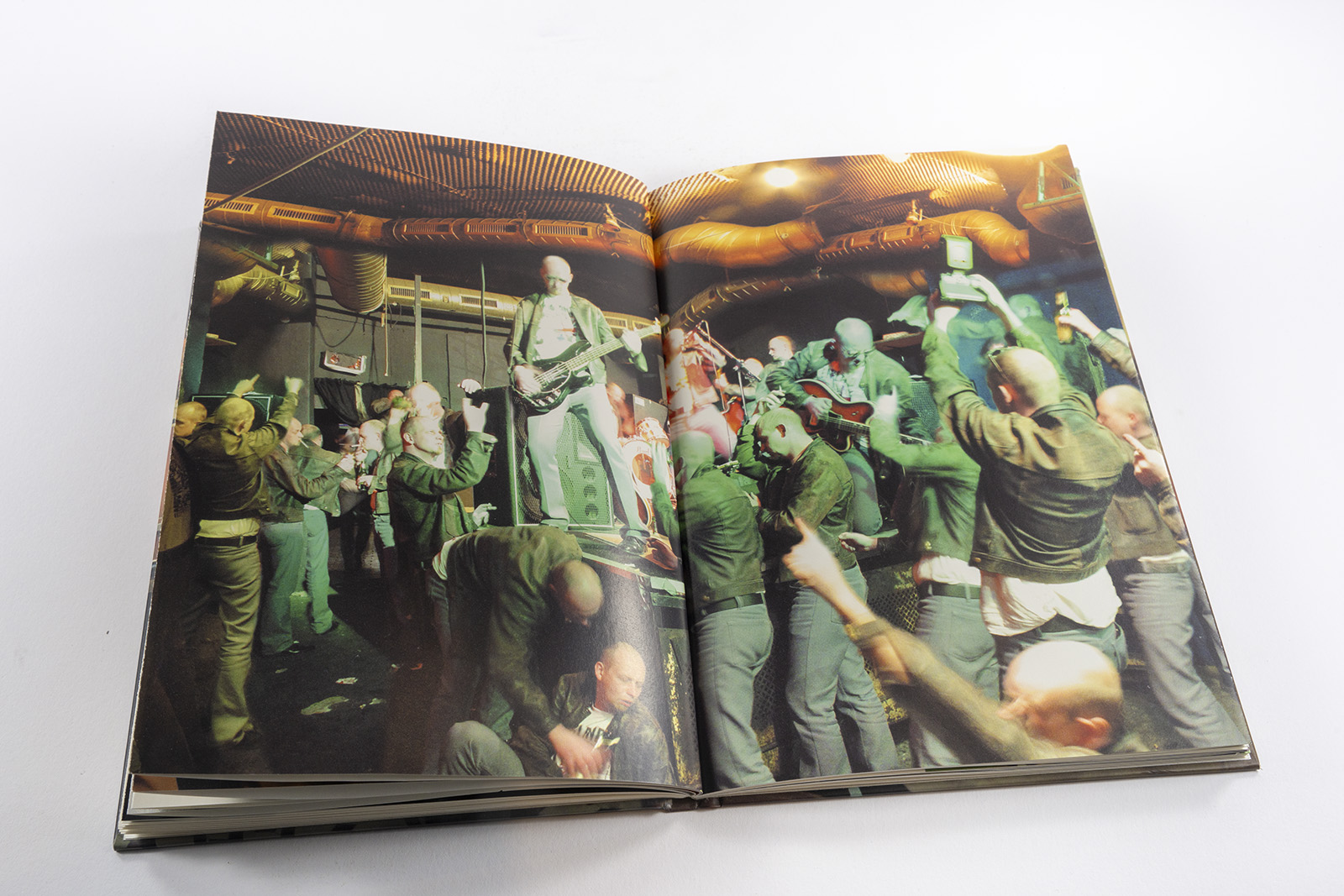

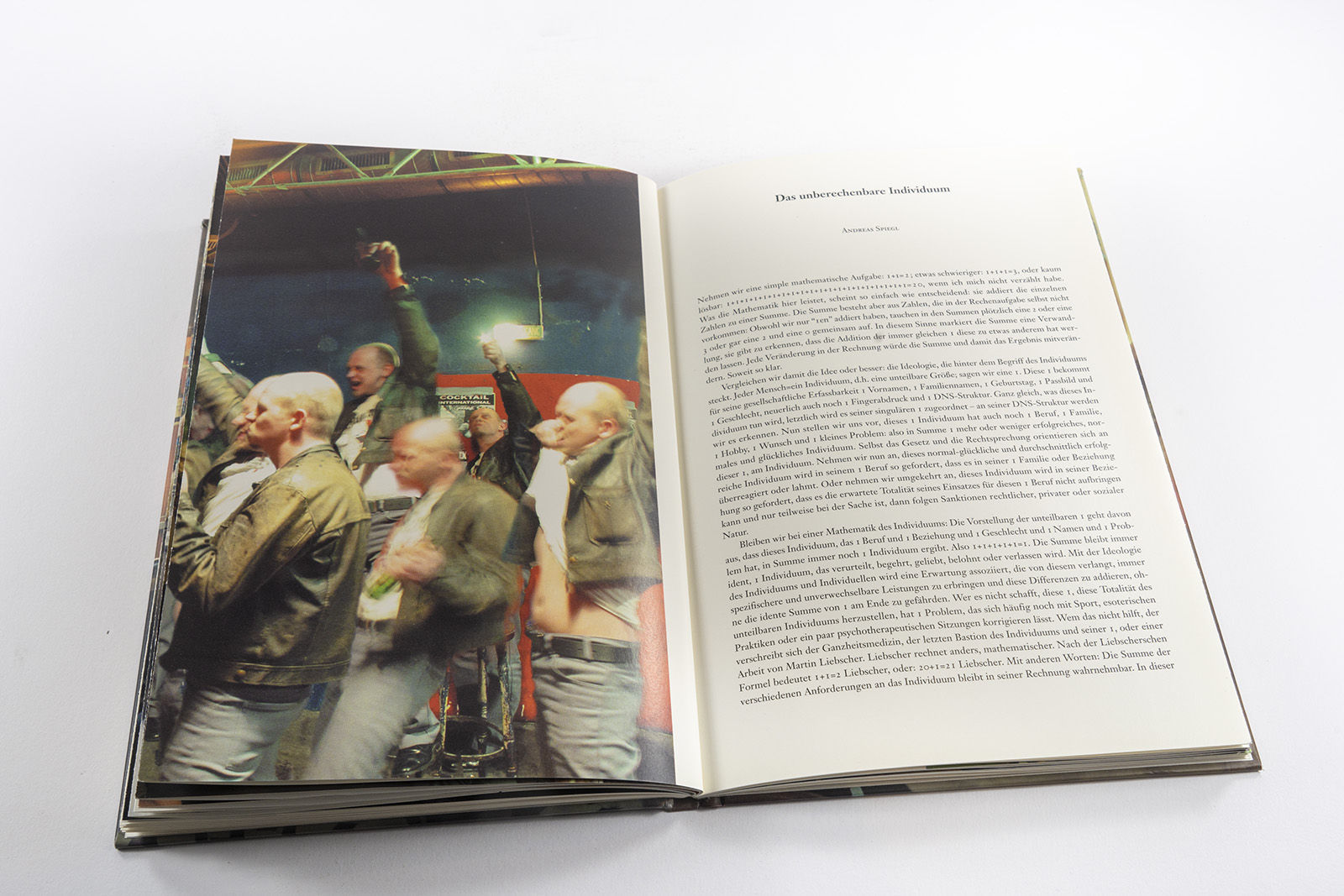

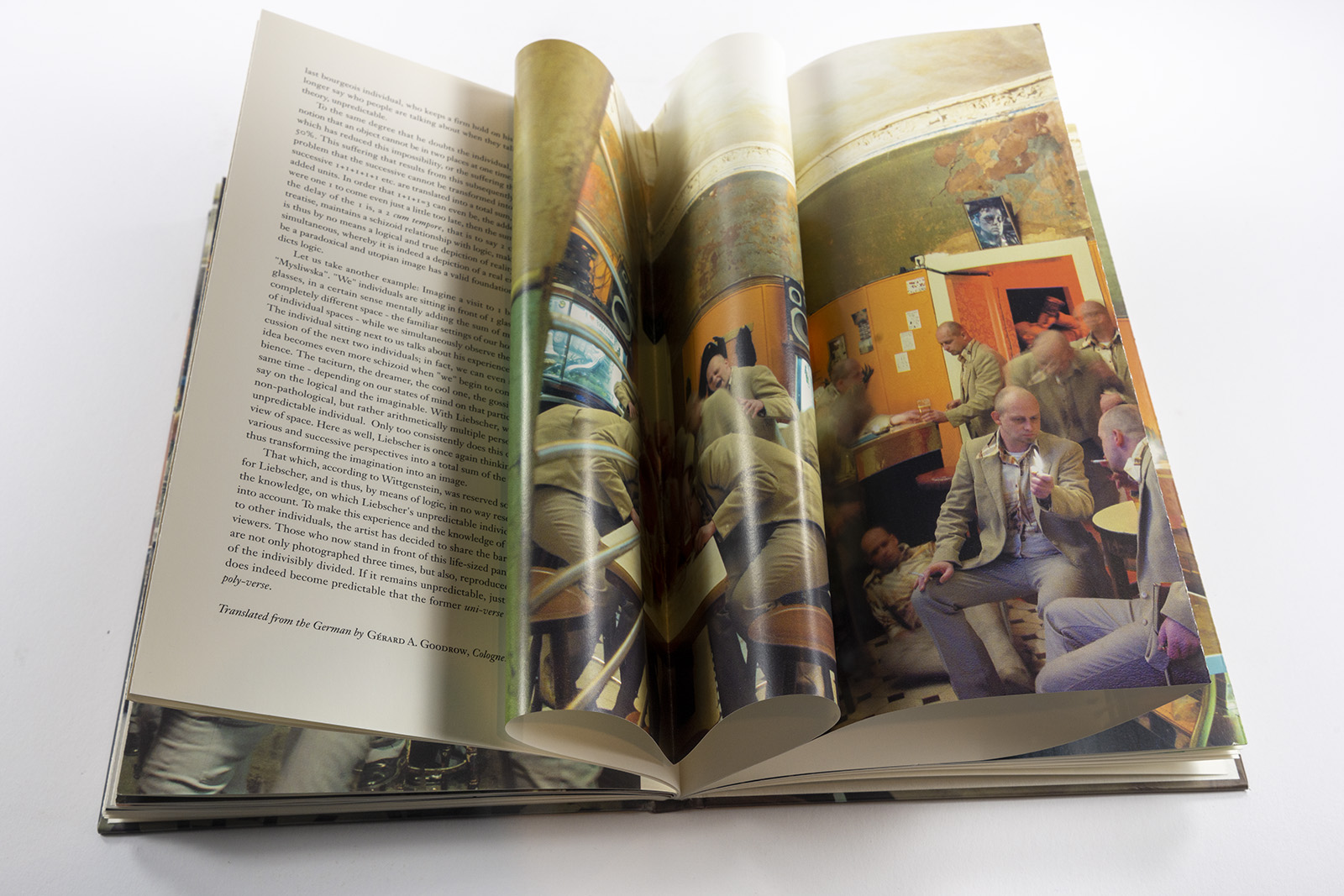

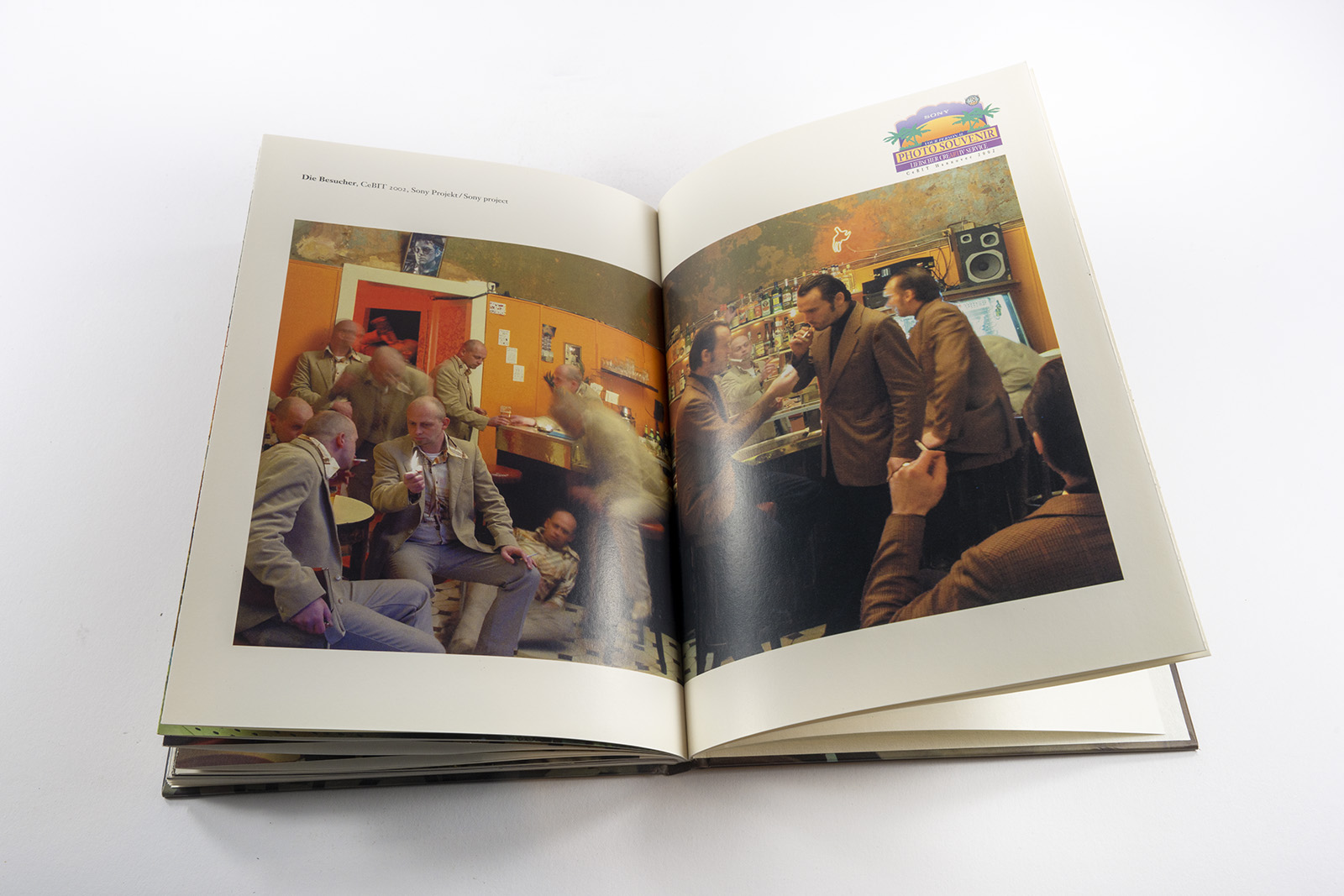

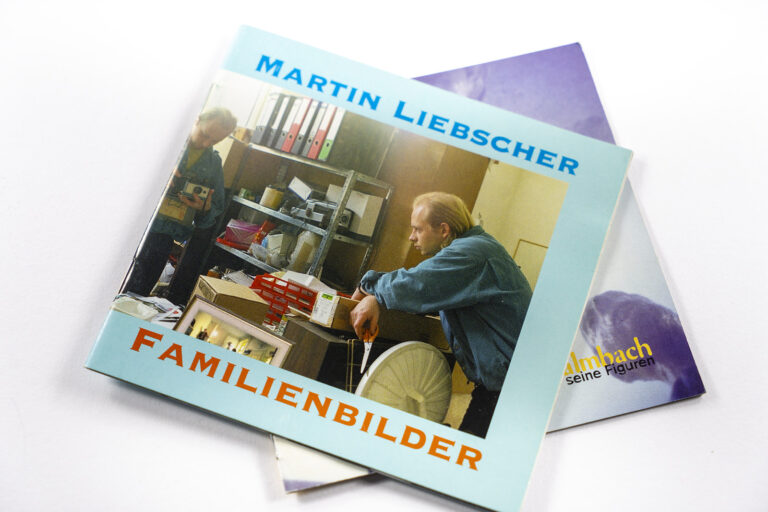

Book with Japanese binding: the panoramic images run over several pages.

Buch mit japanischer Bindung: die panoramischen Bilder laufen über mehrere Seiten.

- Editor: Martin Liebscher, Kehrer Verlag Heidelberg, Cato Jahns

- Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg 2002

- Text: Andreas Speigl

- Design: Martin Liebscher, Kehrer com Heidelberg

- Hardcover

- 16,5 x 23,5 cm

- 42 pages

- Deutsch/Englisch

- ISBN 3-933-257-82-4

Andreas Spiegl

Das unberechenbare Individuum

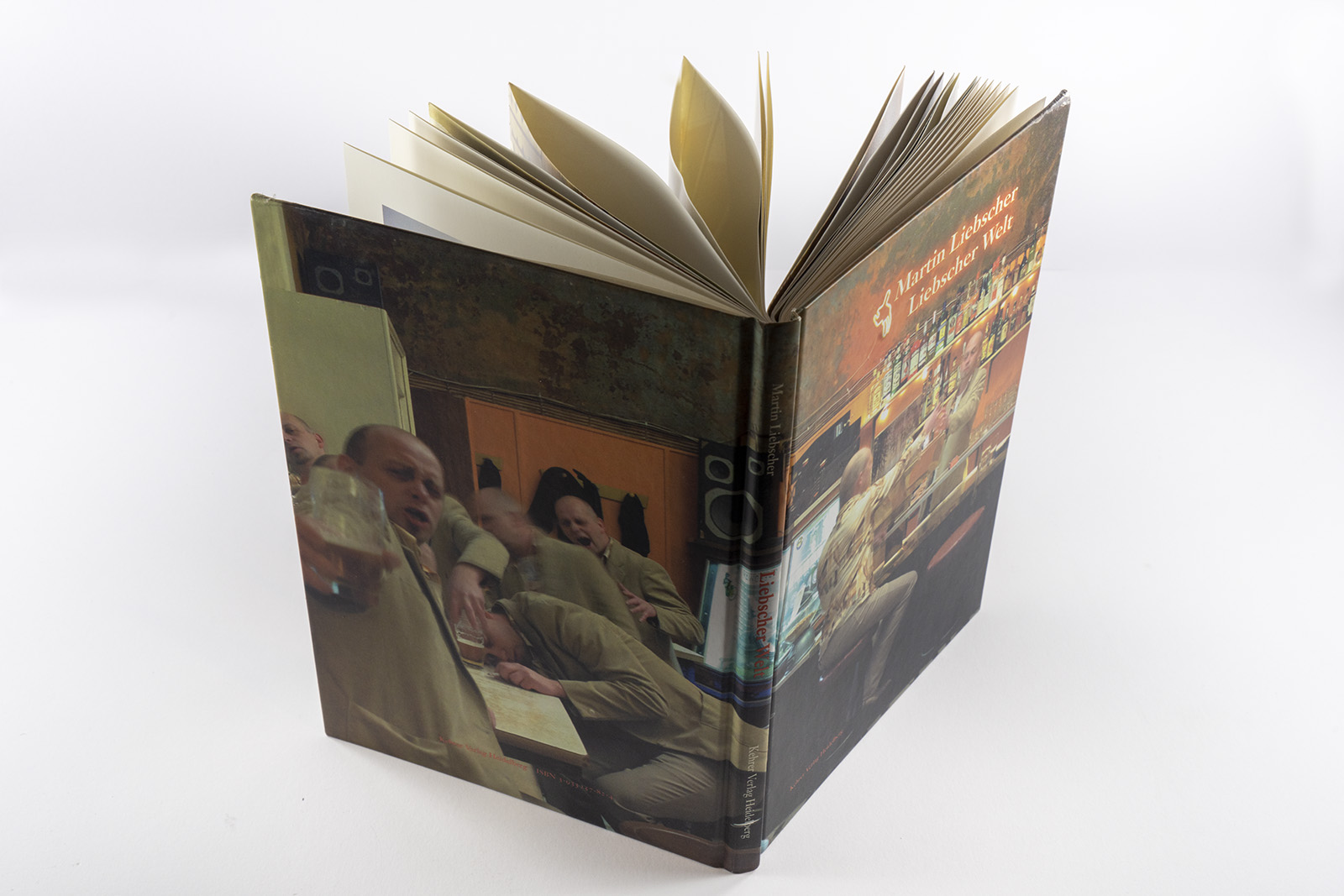

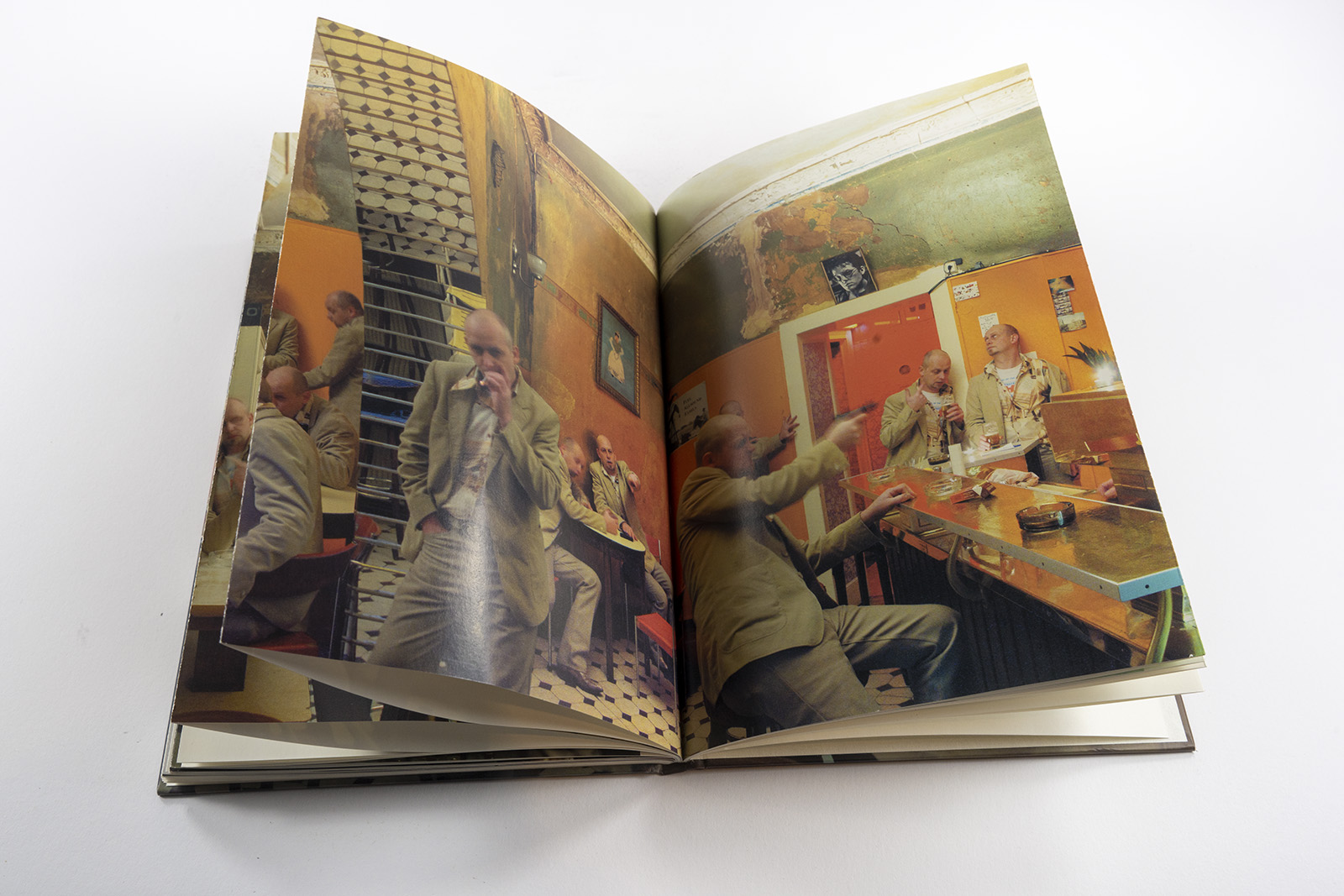

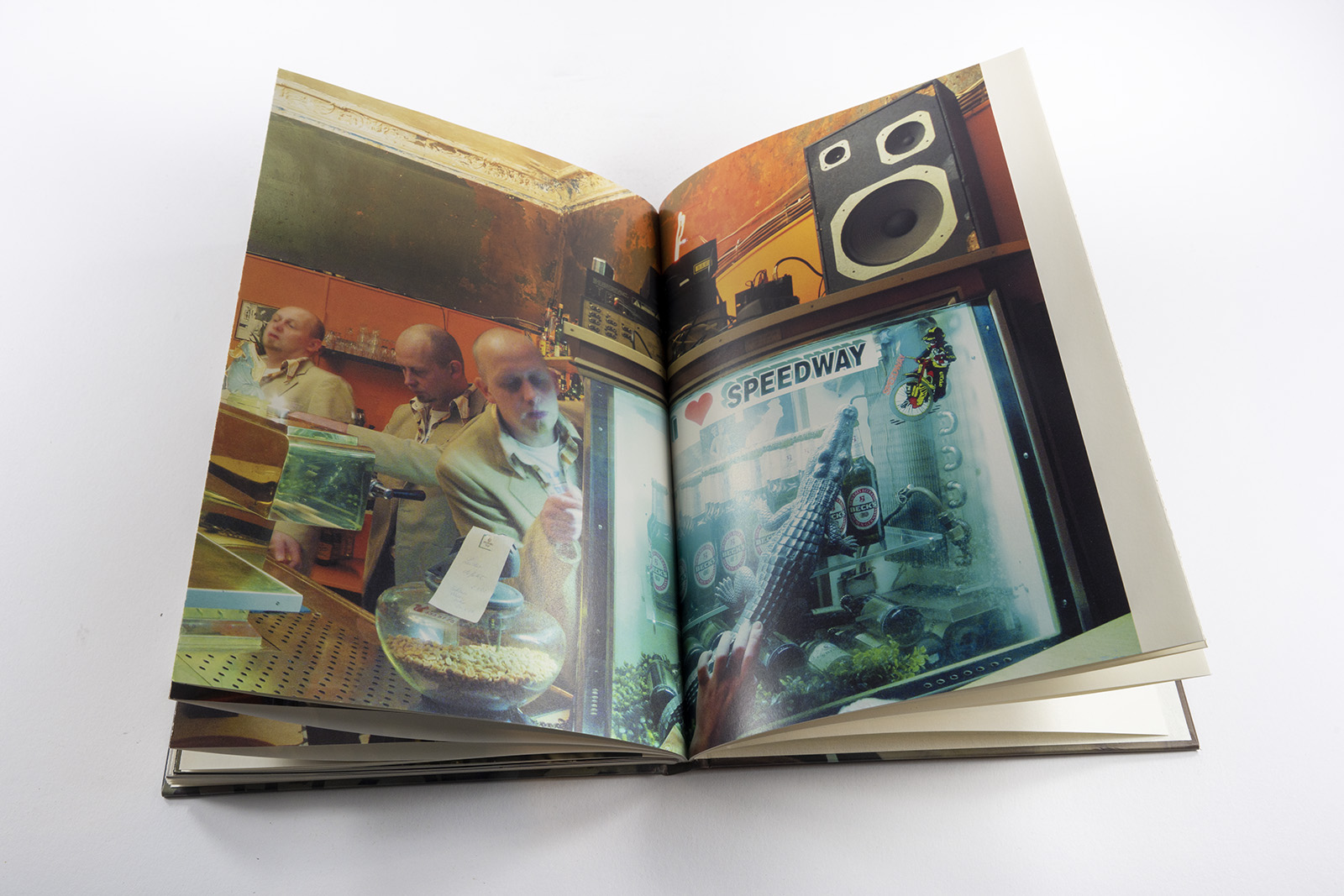

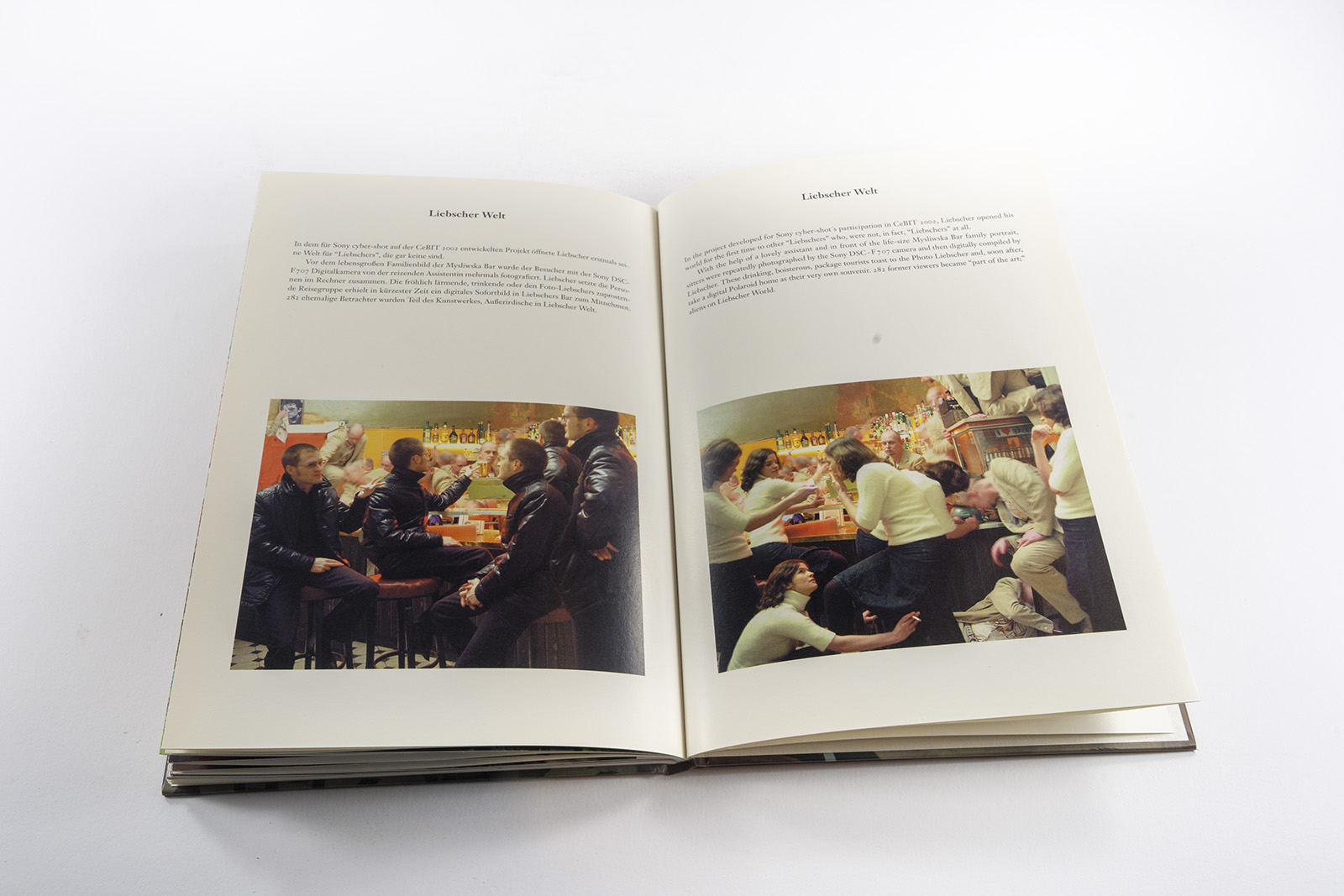

Andeas Spiegl Das unberechenbare Individuum Nehmen wir eine simple mathematische Aufgabe: 1+1=2; etwas schwieriger: 1+1+1=3, oder kaum lösbar: 1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1=20, wenn ich mich nicht verzählt habe. Was die Mathematik hier leistet, scheint so einfach wie entscheidend: sie addiert die einzelnen Zahlen zu einer Summe. Die Summe besteht aber aus Zahlen, die in der Rechenaufgabe selbst nicht vorkommen: Obwohl wir nur “1en” addiert haben, tauchen in den Summen plötzlich eine 2 oder eine 3 oder gar eine 2 und eine 0 gemeinsam auf. In diesem Sinne markiert die Summe eine Verwandlung, sie gibt zu erkennen, dass die Addition der immer gleichen 1 diese zu etwas anderem hat werden lassen. Jede Veränderung in der Rechnung würde die Summe und damit das Ergebnis mitverändern. Soweit so klar. Vergleichen wir damit die Idee oder besser: die Ideologie, die hinter dem Begriff des Individuums steckt. Jeder Mensch=ein Individuum, d.h. eine unteilbare Größe; sagen wir eine 1. Diese 1 bekommt für seine gesellschaftliche Erfassbarkeit 1 Vornamen, 1 Familiennamen, 1 Geburtstag, 1 Passbild und 1 Geschlecht, neuerlich auch noch 1 Fingerabdruck und 1 DNS-Struktur. Ganz gleich, was dieses Individuum tun wird, letztlich wird es seiner singulären 1 zugeordnet — an seiner DNS-Struktur werden wir es erkennen. Nun stellen wir uns vor, dieses 1 Individuum hat auch noch 1 Beruf, 1 Familie, 1 Hobby, 1 Wunsch und 1 kleines Problem: also in Summe 1 mehr oder weniger erfolgreiches, normales und glückliches Individuum. Selbst das Gesetz und die Rechtsprechung orientieren sich an dieser 1, am Individuum. Nehmen wir nun an, dieses normal-glückliche und durchschnittlich erfolgreiche Individuum wird in seinem 1 Beruf so gefordert, dass es in seiner 1 Familie oder Beziehung überreagiert oder lahmt. Oder nehmen wir umgekehrt an, dieses Individuum wird in seiner Beziehung so gefordert, dass es die erwartete Totalität seines Einsatzes für diesen 1 Beruf nicht aufbringen kann und nur teilweise bei der Sache ist, dann folgen Sanktionen rechtlicher, privater oder sozialer Natur. Bleiben wir bei einer Mathematik des Individuums: Die Vorstellung der unteilbaren 1 geht davon aus, dass dieses Individuum, das 1 Beruf und 1 Beziehung und 1 Geschlecht und 1 Namen und 1 Problem hat, in Summe immer noch 1 Individuum ergibt. Also 1+1+1+1+1=1. Die Summe bleibt immer ident, 1 Individuum, das verurteilt, begehrt, geliebt, belohnt oder verlassen wird. Mit der Ideologie des Individuums und Individuellen wird eine Erwartung assoziiert, die von diesem verlangt, immer spezifischere und unverwechselbare Leistungen zu erbringen und diese Differenzen zu addieren, ohne die idente Summe von 1 am Ende zu gefährden. Wer es nicht schafft, diese 1, diese Totalität des unteilbaren Individuums herzustellen, hat 1 Problem, das sich häufig noch mit Sport, esoterischen Praktiken oder ein paar psychotherapeutischen Sitzungen korrigieren lässt. Wem das nicht hilft, der verschreibt sich der Ganzheitsmedizin, der letzten Bastion des Individuums und seiner 1, oder einer Arbeit von Martin Liebscher. Liebscher rechnet anders, mathematischer. Nach der Liebscherschen Formel bedeutet 1+1=2 Liebscher, oder: 20+1=21 Liebscher. Mit anderen Worten: Die Summe der verschiedenen Anforderungen an das Individuum bleibt in seiner Rechnung wahrnehmbar. In dieser Hinsicht ist der additive Prozess in seiner Arbeit nicht nur Ausdruck narzisstischer Selbstbespiegelung (eine humorige Reminiszenz einer Wahrnehmung des Künstlers als letztes Paradeindividuum), sondern auch ein Hinweis auf eine Identitätspolitik, die sich zur Fragmentierung und Partialisierung bekennt. Liebscher ist das letzte bürgerliche Individuum, das an seinem Namen und Abbild festhält, und das erste, das nicht mehr sagen kann, von wem die Rede ist, wenn von ihm gesprochen wird. Gewissermaßen ein Kind der Mengenlehre, unberechenbar. Im selben Maße wie am Individuum zweifelt Liebscher an der Logik, dass ein Ding nicht an zwei Orten gleichzeitig sein kann. Das Mobiltelefon ist eine jener Apparaturen, die diese Unmöglichkeit oder das Leiden an dieser Unmöglichkeit zumindest halbiert. Dieses Leiden an der mithin halbierten Unmöglichkeit basiert auf dem Problem, das Sukzessive nicht in Simultaneität verwandeln zu können. Mathematisch werden das sukzessive 1+1+1+1+1 und so weiter in eine Summe übersetzt, die nun die Gleichzeitigkeit der addierten Größen ausdrückt. Damit 1+1+1=3 sein kann, müssen die addierten 1en gleichzeitig in der 3 enthalten sein; würde eine 1 nur etwas zu spät kommen, dann wäre die Summe eben nur 2 oder je nach Verspätung der 1 eine 2 cum tempore, d.h. 2 komma… Die Kunst, die seit Wittgensteins Traktat ein gespaltenes Verhältnis zur Logik unterhält, machts möglich. Das summarische Bild Liebschers ist dann zwar kein logisches und wahres Abbild der Realität, verwandelt es doch das Sukzessive in Simultanes, dafür aber ein Abbild einer realistischen Befindlichkeit. Was damit als paradoxes und utopisches Bild erscheint, hat sein Reales in der Alltagswirklichkeit, in einem Begehren, das sich an der Logik reibt. Nehmen wir ein weiteres Beispiel: Stellen wir uns den Besuch 1 Bar vor, die bei Liebscher “Mysliwska” heissen könnte: “Wir” Individuen sitzen vor 1 Glas, d.h. wir sitzen vor 1 Glas nach mehreren Gläsern, bilden mental quasi die Summe von mehreren Gläsern, und stellen uns derart vermehrt einen ganz anderen Raum vor — das traute Heim, den Urlaubsort usf., also eine Summe von individuellen Räumen — während wir simultan die uns umgebende Lokalität mit offenen Augen beobachten. Der Nachbar neben uns erzählt von seinen Erlebnissen, während wir gleichzeitig am Gespräch der beiden nächsten Individuen Interesse gefunden haben, ja uns vorstellen können, auch an diesem Disput teilhaben zu können. Noch gespaltener wird diese Vorstellung, wenn “wir” uns überlegen sollten, welche Rollen wir in diesem Ambiente spielen könnten. Den Schweigsamen, den Träumer, den Coolen, den Schwätzer, den Looser, den Star oder alle Versionen zugleich — eine Frage der Tagesverfassung, und eine Frage der Logik, d.h. des Logischen und des Vorstellbaren. Was vorstellbar erscheint, wird bei Liebscher sichtbar: Eine nicht krankhaft sondern rechnerisch multiple Persönlichkeit, als Summe einer Mathematik des unberechenbaren Individuums. Nur zu konsequent impliziert dieser Perspektivenwechsel auch eine Mehransichtigkeit des Raumes. Liebscher denkt auch hier wieder mathematisch, und verwandelt die verschiedenen und sukzessiven Perspektiven in eine Summe simultaner Wahrnehmbarkeit des Verschobenen: die Einbildung in eine Abbildung. Was nach Wittgenstein der Kunst vorbehalten war, ist nach Liebscher deshalb noch lange nicht und schon gar nicht logischerweise dem Künstler allein vorbehalten. Noch dazu, wo die Erkenntnisse, auf die Liebschers unberechenbares Individuum baut, der Alltagserfahrung Rechnung tragen. Um diese Erfahrung und Erkenntnis der Unberechenbarkeit und Vermehrung auch anderen Individuen zugänglich zu machen, hat sich der Künstler entschlossen, die oben erwähnte Bar mit seinen BesucherInnen zu teilen. Wer nun vor dieses lebensgroße Panorama der Unberechenbarkeit und Vermehrung tritt, wird nicht nur dreimal abgelichtet, sondern derart reproduziert in die Gemeinde der unteilbar Geteilten aufgenommen. Bleibt es auch unberechenbar, wer sich mit diesem Individuum identifiziert, so wird berechenbar, dass sich das einstige Universum von Martin Liebscher in ein Polyversum öffnen wird.

Andreas Spiegl

The Unpredictable Individual

Take the simple mathematical equation: 1+1=2; somewhat more difficult: 1+1+1=3, or barely solvable: 1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1=20, if I am not mistaken. What mathematics achieves here seems as easy as it is decisive: it adds the individual numbers to arrive at a total sum. But the sum itself also consists of numbers, which do not appear themselves in the arithmetical task: although we have only added „1s“, in the sums we suddenly find a 2 or a 3 or even a 2 and a 0 together. In this sense, the sum describes a transformation; it demonstrates that the addition of the same 1 allowed this 1 to become something entirely different. Each change in the calculation would thus have an effect on the sum and, with this, the final result. So far, so good. Let us compare this with the idea, or better the ideology, which lies behind the concept of the individual. Every person = individual; that is to say an indivisible entity, such as, let us say, a 1. To socially record it, this 1 is then allocated 1 first name, 1 family name, 1 birthday, 1 passport photo and 1 gender, and recently even 1 fingerprint and 1 DNS code. Completely and utterly regardless of what this individual does, in the final analysis it is categorised according to its singular 1 – we can recognise this in its DNS code. Now let us suppose that this 1 individual also has 1 career, 1 family, 1 hobby, 1 wish and 1 small problem: that is to say, in total 1 more or less successful, normal and happy individual. Even the law and the administration of justice orientate themselves according to this 1, that is to say to this individual. But let us now assume that this normal, happy and more or less successful individual is so challenged in his 1 career that it overreacts or even becomes paralysed in its 1 family or relationship. Or let us assume the opposite, that this individual is so challenged in its relationship that it cannot summon up the expected totality of its investment for this 1 career and thus cannot keep its mind on the job at hand. As a consequence, it becomes faced with particular sanctions, be these of a legal, private or social nature. Let us stick with the mathematics of the individual: The concept of the indivisible 1 presupposes that this individual, which possesses 1 career and 1 relationship and 1 gender and 1 name and 1 problem, still adds up in the end to only 1 individual. Thus, 1+1+1+1+1=1. The total sum always remains identical: 1 individual, who is condemned, desired, loved, rewarded or abandoned. With the ideology of the individual and the individualistic one associates an expectation, which demands of the individual that it produce increasingly more specific and unmistakable results, and to add these differences together without endangering the identical sum of 1 at the end. Those who cannot do this, who cannot finish off with this 1 at the end, who cannot produce this totality of the indivisible individual, has 1 problem, which can often be corrected with the help of sports, esoteric practices or a few psychotherapeutic sessions. Those who cannot be helped by this devote themselves to holistic medicine, the last bastion of the individual and its 1 – or to a work by Martin Liebscher. Liebscher adds differently, more mathematically. According to Liebscher’s formula, 1+1=2 Liebscher, or 20+1=21 Liebscher. In other words: the sum of the various demands made on the individual remains perceptible in the equation. In this sense, the additive process in his work is not only an expression of narcissistic self-reflection (a humorous reminiscence of a perception of the artist as the last para-individual), but also a reference to a policy of identity that bears witness to fragmentation and partialisation. Liebscher is the last bourgeois individual, who keeps a firm hold on his name and likeness, and the first who can no longer say who people are talking about when they talk about him. In a certain sense a child of set theory, unpredictable. To the same degree that he doubts the individual, Liebscher also doubts the logic behind the notion that an object cannot be in two places at one time. The mobile telephone is one such apparatus, which has reduced this impossibility, or the suffering that results from this impossibility, by at least 50%. This suffering that results from this subsequently 50% reduced impossibility is based on the problem that the successive cannot be transformed into simultaneity. Mathematically speaking, the successive 1+1+1+1+1 etc. are translated into a total sum, which now expresses the simultaneity of the added units. In order that 1+1+1=3 can even be, the added 1s must simultaneously exist within the 3; were one 1 to come even just a little too late, then the sum would only be 2 or, depending on how long the delay of the 1 is, a 2 cum tempore, that is to say 2 comma… Art, which, since Wittgenstein’s treatise, maintains a schizoid relationship with logic, makes this possible. Liebscher’s summary image is thus by no means a logical and true depiction of reality, since it transforms the successive into the simultaneous, whereby it is indeed a depiction of a real existing situation. What appears as a result to be a paradoxical and utopian image has a valid foundation in everyday reality, in a desire that contradicts logic. Let us take another example: Imagine a visit to 1 bar, which, with Liebscher, might be called „Mysliwska“. „We“ individuals are sitting in front of 1 glass, that is to say in front of 1 glass after many glasses, in a certain sense mentally adding the sum of many glasses, and we increasingly imagine a completely different space – the familiar settings of our home, a holiday resort etc., that is to say a sum of individual spaces – while we simultaneously observe the bar that surrounds us with eyes wide open. The individual sitting next to us talks about his experiences, while we simultaneously listen to the discussion of the next two individuals; in fact, we can even imagine participating in this dispute. This idea becomes even more schizoid when „we“ begin to consider which roles we could play in this ambience. The taciturn, the dreamer, the cool one, the gossip, the looser, the star, or all versions at the same time – depending on our states of mind on that particular day, and depending on logic, that is to say on the logical and the imaginable. With Liebscher, what appears imaginable becomes visible: a non-pathological, but rather arithmetically multiple personality, as the sum of a mathematics of the unpredictable individual. Only too consistently does this change in perspective also imply a multiple view of space. Here as well, Liebscher is once again thinking mathematically, and thus transforms the various and successive perspectives into a total sum of the simultaneous perceptibility of the shifted: thus transforming the imagination into an image. That which, according to Wittgenstein, was reserved solely for art, does not in any way have be so for Liebscher, and is thus, by means of logic, in no way reserved solely for the artist. Especially when the knowledge, on which Liebscher’s unpredictable individual is founded, takes everyday experience into account. To make this experience and the knowledge of unpredictability and multiplicity accessible to other individuals, the artist has decided to share the bar mentioned above with other visitors, his viewers. Those who now stand in front of this life-sized panorama of unpredictability and multiplicity are not only photographed three times, but also, reproduced this way, integrated into the community of the indivisibly divided. If it remains unpredictable, just who will identify with this individual, it does indeed become predictable that the former uni-verse of Martin Liebscher will open up into a poly-verse. Translated from the German by Gérard A. Goodrow, Cologne.